by Max Kornblith

“If you don’t like what’s being said, then change the conversation” – Don Draper

“If you don’t like what’s being said, then change the conversation” – Don Draper

In this essay:

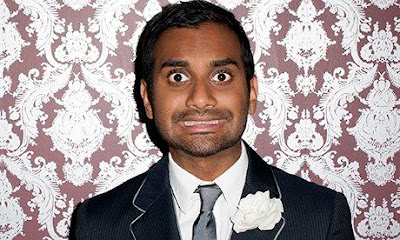

Aziz Ansari on luck

and dating

My “passion dilemma”

The unacknowledged

co-conspirator in life

Living with messiness

The formula for love

In the midst of a course on probability, my college

statistics professor revealed the “solution” to the problem of dating. He told

us that, upon granting a few assumptions*, search theory—the statistical

toolset honed for the rapid selection of a proverbial needle from a haystack—suggests

an optimal approach to picking a mate. Proceed through one third of the maximum

number of partners you expect to have the opportunity to date in life, he

instructed, and then, having used this experience to set a baseline, settle

down with the next candidate whose overall quality exceeds that of anyone

you’ve already dated. This approach balances the risk of settling for what’s

too easily available versus that of holding out too long for perfection.

The proposal may be computationally simple, but it raises irksome

questions:

How will it change my worldview to believe that my “soul mate” and I

have found each other thanks to something other than an inevitable emotional-magnetic

pull? Could it be problematic to see the match instead as the logical outcome

of a specified procedure, an algorithm? And how do I tell a meaningful story of

such a major life event if it’s seen as the contingent outcome of a

probabilistic process, one that could have gone differently?

This potential for discomfort is illustrated by a bit

performed by comedian and Parks and

Recreation star Aziz Ansari. He tells of a friend who found love through

online dating. To pair with one specific individual from the massive universe

of potential mates online, Ansari says, is “kind of a romantic thing, so I

asked him, what'd you search? And he says, 'Jewish, and my zip code.'” To

Ansari, this is a troubling answer. “That's how I found a Wendy's a few weeks

ago… [but] I got some nuggets [and] he got his wife the exact same way!"

In other words, if Ansari had happened to type something slightly different

maybe he would’ve ended up at Burger King and his life would’ve gone on as

before. But for his friend a few different keystrokes would’ve meant life with

a different soul mate. Weird.

Are you and your job a

love match?

If the winding road to love is the greatest veiled search

theory problem most young people face, the second greatest such challenge—for

those so lucky—may be choosing a career. The two processes can have a lot in

common: An almost endless universe of (hypothetical) options, two sides each navigating

a trade-off between holding out for perfect and settling for good enough, the

nagging pressure to just pick something already and stick with it.

And then there’s the language of “passion.” In job-hunting

as in dating, searchers look for a firm whose unique suitability for them

resonates emotionally. And firms seek something similar in their candidates. One

recent job posting I happened upon sought only an individual for whom this was

their “dream job,” and all others apparently need not bother to apply.

It’s here that I should mention that I’ve previously gotten

into some trouble for questioning the language of “passion” in career choice. In

late 2012 I wrote an

e-mail to blogger and economist Tyler Cowen that focused on two separate

questions. The first question I posed was what discussion “passion” in a career

choice context meant to him as a social scientist. The second question I put

forward, and the one that subsequently gained traction, was how I personally should

approach finding the right job and career given that I didn’t have the vision of a specific desired

outcome that comes with speaking the language of “passion.”

|

| Bangkok Golden Thai in Fairfax, Va. Site of the 2014 academic panel put on by GMU economists on the topic of my career. |

According to NPR’s Planet Money, which subsequently covered

the exchange, that latter question placed me in an unfortunate if not uncommon category of

young people whose lack of a driving vocational passion leaves them helpless to

determine a suitable career.

But in hindsight, my question was perhaps best approached

via search theory: More than anything I was seeking an outsider’s read on how

to optimize my career search. My lack of one driving “passion” doesn’t mean I

don’t have particular values and goals against which I evaluate a job—for me

these values include the opportunity to learn, to take on responsibility, and

to work with high-quality and empathetic coworkers in a focused environment. I refuse, though, to restrict my

application of these criteria within only a limited subset of potential careers.

And, as in any maximization problem, an inability to constrain along any

particular dimensions multiples the complexity of the problem.

The unacknowledged

co-conspirator

A

number of people—acquaintances and strangers—reached out to me with advice

after hearing the NPR story. In these and other conversations I was struck by

the number of individuals—entrepreneurs, financial professionals, academics—who

have told me they didn’t know what they wanted to do until they stumbled upon

it. If such stories are representative, it’s hard to not acknowledge that a lot

of people may be in the “wrong” job just for not having run into the right one

at the right time.

More than 150 years ago a young William James lamented the

inherent gamble that comes with picking a career. “The worst of this matter,” wrote

James, long before he’d become a celebrated social scientist, “is that

everyone must more or less act with insufficient knowledge—‘go it blind,’ as

they say. Few can afford the time to try what suits them.” Necessarily, in such

cases, a lot is left up to chance and contingency. (It seems to have worked out

for James.)

This

lack of foreknowledge, over what will and won’t suit us, makes a good approach

to job-seeking—a quality search algorithm if you will—all the more important.

Imagine playing a hand of hold-‘em poker without knowing in advance the ranking

of the hands.

But to

engage with alternate search approaches is also to acknowledge that, as

in a hand of poker, many life outcomes are probabilistic; they depend on both

judgment and luck. If I could re-run my life again, and make the exact same

decisions, I might reach a different outcome thanks to the bouncing balls in

life’s lottery. A probabilistic reading translates the reality of my present or

future circumstances into the output of a process that depends on my past, my

personal decisions, external circumstances, and—significantly—a degree of

random noise.

That may be a scary thought: It’s easy to acknowledge chance

as the reason that small things happen the way they do—for instance how I might

see a particular movie instead of another because the first is sold out. But it

can create discomfort—like Aziz Ansari’s above—to acknowledge the role of luck

in how major things work out in life, things like families and careers and life

satisfaction.

A less-than-clean conclusion

An ambitious existentialist might mention at this point the

sheer improbability of each one of us individually coming to inhabit our

universe in the first place. The fact of my very being has depended on the

precise biographical path of each one of my forebears, and—even more

improbably—on one singular outcome from competition between four gazillion

gametes.**

Could this gestational implausibility sit at the root of

human anxiety at life’s uncertainness? Without taking it that far, the

undeniable truth is that life is messy, with luck as an input into many of its

outcomes. There is value in acknowledging this messiness, both in the world’s

processes and in one’s self, and a danger in dismissing it.

An intolerance for messiness creates risks. One of my

favorite critics of academia, William Dersciewitz, writes

of his time teaching Ivy League undergraduates for whom “[t]he prospect of

not being successful terrifies them

[and] disorients them.” These kids don’t take risks—they don’t take chances—because doing so would admit not

just the world’s imperfection but their own: Stepping from one’s comfort zone

into James’s unknown is an admission that the whole world is not in fact known

to the person doing the stepping. Aversion to this fact may be what leaves students

“content to color within the lines” (Dersciewitz’s words) of an educational and

career hierarchy ranked by prestige and selectivity.

|

| Dersciewitz is also known for struggling to find common topics of conversation with a plumber, who may not have been as friendly as the one in this stock photo. |

So how might one avoid the apparent pitfalls that follow

from a fear of messiness and chance? In my own recent life, I have tried to use

the messiness of the world as a spur toward experimentation. I’ve left good

jobs and relinquished

nice apartments. I’ve traveled well and read well and dined well. I’ve attempted

to stretch out life’s experimental phase—that supposed first third—and to

acknowledge the role of chance without using it as an excuse to non-commitment.

I hope I’ve done all this without abandoning a strong emotional investment in and

personal responsibility for outcomes.

And is it working for me? Maybe, if I’m lucky.

And is it working for me? Maybe, if I’m lucky.

No comments:

Post a Comment